What Pediatric Occupational Therapy Is (and Isn’t)!

By Michaela E. Gordon, OTR/L

Throughout my time as an OT, I have worked hard to find ways to capture, explain, and demonstrate the full scope of occupational therapy. I think back to all the settings I have worked in and how I worked as an occupational therapist in those settings/systems. Each setting taught me something new that I carried into the next—broadening my understanding and deepening my practice as an OT. Here are some examples from my experience as an OT over the years:

- Mental Health Center: Collaborated with a multidisciplinary team of medical professionals to discuss cases and coordinate care, facilitated self-care and life-skills groups, and developed sensory-based programs to support regulation and coping.

- Pediatric Burn Hospital: Fabricated splints in the operating room to support long-term range of motion in the upper extremities, fitted facial orthoses and pressure garments to minimize scarring, developed adaptive devices for self-care tasks, and provided emotional support to patients and families navigating recovery.

- Hospital Setting: Supported infants in the NICU to promote feeding and sensory regulation, conducted neuro-motor and self-care assessments for adults in acute and subacute units, and designed discharge plans to promote safe transitions home or to other care facilities.

- Nursing Homes: Addressed memory and cognitive strategies for daily routines, and implemented strength, coordination, and range-of-motion programs to improve independence in self-care and mobility.

- School for Children with Autism: Collaborated closely with a team of medical and educational professionals to provide sensory–motor, social–emotional, and self-care interventions; trained parents and teachers on carryover strategies; and supported community participation through vocational and independent-living experiences such as starting jobs at local businesses, shopping, money management, and dining out.

- Public Schools: Conducted school-based assessments, provided direct services for students with identified needs, consulted with teachers to support students who did not qualify for services, and participated in IEP meetings to collaborate with families and interdisciplinary team members.

- Aquatic Therapy: Used neurodevelopmental and sensory-based techniques in the water to promote regulation, strength, coordination, and safety.

- Early Intervention: Provided home- and community-based services to infants and toddlers, focusing on early sensory–motor, fine motor, and self-care development. Supported parents and caregivers through education, hands-on training, and individualized home programs.

- Clinic-Based Practice: Served children of all ages, with an emphasis on sensory–motor development, fine motor skills, and self-regulation. Ran early intervention and social skills groups, collaborated with other professionals (e.g., PTs, SLPs), and provided home programming and parent training to promote skill carryover.

- Private Practice (In-Home): Worked with families in their natural environments to support sensory–motor, self-care, social–emotional, and executive functioning skills. Designed individualized home programs, provided parent education, and integrated holistic interventions such as aquatic therapy and craniosacral therapy.

- Private Practice (Office Setting): Offer similar services to in-home care with expanded access to specialized equipment and materials, incorporating sensory–motor play, regulation-based supports, and holistic interventions.

- Community Outreach: Partner with schools and community centers to educate families and professionals about occupational therapy, facilitate support groups, help with developing community programs, and promote public awareness through blogs, social media, and outreach materials.

Each of these settings offered unique insights into how occupational therapy helps individuals adapt, recover, and grow. Whether in hospitals, schools, clinics, or the community, the common thread is helping people participate more fully and meaningfully in their everyday lives.

As you can see, the role of the OT can widely vary based on the setting/system, the role of the other professionals involved, and the experience of the therapist. I’m sure you could meet another OT that will tell you other ways they have worked in the field.

In terms of pediatrics, I would say pediatric occupational therapists are most well-known for helping kids with developing sensory and handwriting skills. However, we do so much more than that! I find that once an OT starts working with other professionals and families, they are often surprised to find out all the ways we can help kids and families.

Occupational therapy is one of the most versatile fields in healthcare. While it overlaps with psychology, physical therapy, and speech therapy, OT is distinct in its focus on helping children participate in the many occupations of daily life—everything from getting dressed and playing, to learning, socializing, and building independence. Our goal is to strengthen the skills that make everyday living meaningful and successful.

The Domain of Occupational Therapy (AOTA, OTPF-4)

According to the American Occupational Therapy Association (AOTA), the domain of occupational therapy outlines the full range of areas OTs address to support meaningful participation in daily life. This framework is described in the Occupational Therapy Practice Framework: Domain and Process, 4th Edition (OTPF-4, 2020).

The domain is composed of five interrelated areas:

1. Occupations – The everyday activities people want, need, or are expected to do. For children: play, education, self-care, rest/sleep, and social participation.

2. Client Factors – The underlying capacities that influence performance. Includes values, beliefs, body functions (sensory, cognitive, emotional, motor), and body structures.

3. Performance Skills – The observable, goal-directed actions used in daily life. Includes motor skills (e.g., posture, coordination), process skills (e.g., organization, attention), and social interaction skills.

4. Performance Patterns – The habits, routines, and roles that structure daily life. For children, these may include school routines, bedtime rituals, and family roles.

5. Contexts – The environmental and personal factors that influence participation. Includes physical, social, cultural, temporal, and virtual environments.

Together, these areas describe the scope of what OTs assess and address—providing a holistic, person-centered framework that supports participation across all areas of life.

In the following sections, I describe what this looks like in practical terms—how occupational therapists may help children and families build the skills and supports they need for everyday life.

What OT Is

Occupational therapists support the whole child—addressing interconnected systems of sensory, motor, cognitive, and emotional development. These domains are interdependent and together build a child’s capacity to learn, connect, and thrive in daily life. Below are the primary areas pediatric OTs focus on when helping children reach their fullest potential.

Sensory Integration and Other Sensory-Based Approaches

Occupational therapists (OTs) assess and treat sensory integration challenges using evidence-based approaches that help children process sensory input more effectively and participate more fully in everyday activities such as play, learning, and self-care. One of the most established models is Ayres Sensory Integration® (ASI), developed by Dr. A. Jean Ayres, which focuses on enhancing the brain’s ability to organize and interpret sensory information through play-based, child-led activities.

In addition to ASI, OTs may draw from a range of sensory-based and sensory-informed frameworks to address individual differences in regulation and participation. These may include the Sensory Processing Model (Winnie Dunn), which helps identify sensory seeking or avoiding patterns to guide environmental adaptations; The Alert Program® (“How Does Your Engine Run?”) and The Zones of Regulation®, which teach children to recognize and manage their arousal states; and the Sensory Diet Framework (Patricia Wilbarger), which provides structured daily sensory activities to promote attention and self-regulation.

OTs may also incorporate specific sensory-based modalities—such as the Wilbarger Deep Pressure and Proprioceptive Technique (Brushing Protocol), Therapeutic Listening® (Sheila Frick), and Astronaut Training, which integrates vestibular, visual, and auditory processing—when clinically appropriate and with specialized training.

All of these approaches are used within an individualized, occupation-centered treatment plan that supports the child’s ability to regulate, attend, and engage meaningfully in daily routines across home, school, and community settings.

Gross Motor & Physical Development

Occupational therapists address foundational movement skills that support a child’s ability to play, learn, and participate in daily life. This includes developing balance, coordination, postural control, strength, endurance, and body awareness.

A core focus of gross motor development is bilateral coordination—helping the left and right sides of the body work together in an organized way. OTs also support motor planning, or the ability to generate motor ideas, plan and sequence actions, and carry them out with timing and fluidity.

Through engaging, play-based movement activities, children build the gross motor foundations they need to participate in functional tasks at home, school, and in the community—from climbing and playground play to navigating hallways, carrying materials, and maintaining posture during classroom activities.

Fine Motor & Visual–Motor Skills

Occupational therapists help children develop precise hand movements, coordination, and control that support participation in everyday activities such as dressing, feeding, writing, and play. This includes building hand strength, grasp patterns, in-hand manipulation, and bilateral coordination for tasks that require both hands to work together.

At the fine motor level, OTs also address motor planning—helping children generate ideas, plan and sequence actions, and carry them out smoothly with appropriate timing and fluency. This process allows children to approach fine motor tasks such as cutting, coloring, writing, manipulating small toys, and using everyday objects like containers and bags with greater confidence and efficiency.

OTs also support visual–motor integration, helping children coordinate what they see with how they move. These skills are essential for tasks like handwriting, lining up numbers for math, completing mazes or tracing paths, and connecting dots—all of which build the foundation for academic success and everyday functional performance.

Through engaging, play-based activities, OTs help children strengthen fine motor control and visual–motor coordination so they can participate more fully in classroom, play, and self-care tasks with precision, confidence, and independence.

Visual–Perceptual & Oculomotor Skills

Occupational therapists help children develop the visual foundations needed for learning, play, and everyday functioning. This includes both oculomotor control—how the eyes move—and visual–perceptual processing—how the brain interprets what the eyes see.

Oculomotor skills involve the ability to track moving objects, visually shift from point to point, adjust focus between near and far distances, and move the eyes independently from head movements. These skills are essential for reading, writing, copying from the board, ball skills, and navigating environments safely and efficiently.

In addition to oculomotor control, OTs address visual–motor integration (coordinating visual input with motor output) and broader visual–perceptual skill development. These include the ability to recognize and remember visual details, distinguish forms and symbols, perceive spatial relationships, and identify objects within complex backgrounds. Together, these ‘motor-reduced’ visual-perceptual skills—such as visual discrimination, memory, spatial awareness, form constancy, sequential memory, figure-ground, and visual closure—help children process visual information accurately and efficiently.

Through individualized, activity-based intervention, OTs strengthen the connection between vision, movement, and perception—helping children participate more successfully in classroom, play, and daily life tasks.

Cognition & Executive Functioning

Occupational therapists help children strengthen the mental skills that allow them to plan, organize, remember, and carry out daily tasks effectively. These executive functions support participation in learning, play, and self-care routines.

OTs work with children on skills such as attention, memory, organization, sequencing, and problem-solving—all of which help them stay focused and complete tasks from start to finish. Intervention often involves teaching children how to visualize their day and break larger tasks into smaller, more manageable steps.

Examples of OT support in this area include:

– Using timers, visual schedules, and checklists to help children understand routines and transitions.

– Supporting the organization of living spaces, school areas, and materials such as desks, lockers, and backpacks.

– Teaching children to sequence tasks—like getting dressed, packing for school, or following multi-step classroom directions—in a logical and efficient order.

– Using memory strategies to help recall important information such as days of the week, home addresses, or phone numbers.

– Encouraging self-monitoring and task persistence—helping children notice when they are distracted, return to the task, and complete it successfully.

By fostering these cognitive and executive function skills, occupational therapists help children become more independent, confident, and capable of managing their responsibilities at home, school, and in the community.

Play, Social Participation, and Social–Emotional Development

Play is a child’s most natural occupation and the foundation for learning, connection, and emotional growth. Occupational therapists use play-based interventions to build the skills children need to engage meaningfully with their world—socially, emotionally, and behaviorally.

Through play, OTs support children in developing emotional regulation, social communication, relationship-building, problem-solving, and flexibility. Play provides a safe, motivating space to practice managing frustration, coping with challenges, and taking turns or sharing with peers.

OTs also help children recognize and express emotions appropriately, read nonverbal cues, and develop empathy and self-awareness. Using frameworks such as The Zones of Regulation®, The Alert Program®, and other self-regulation models, therapists teach children to identify body cues, regulate energy levels, and apply calming or alerting strategies to meet the demands of different environments.

In this way, play becomes a powerful medium for developing social participation, emotional understanding, and self-regulation—allowing children to practice these essential life skills naturally within joyful, meaningful experiences.

OTs also collaborate with caregivers and educators to ensure that play and social–emotional strategies generalize across home, school, and community settings.

By fostering joyful, connected participation, occupational therapy helps children build the emotional resilience and social confidence needed to thrive in relationships and in life.

Behavioral Management

Occupational therapists actively address behavior as part of a child’s ability to participate in daily life. Rather than viewing behavior as something to “fix,” OTs understand it as a form of communication about a child’s sensory, emotional, cognitive, or environmental state. Often, maladaptive behaviors emerge in response to underlying developmental challenges and/or relational or social-environmental factors. As those foundational skills strengthen, OTs help children learn and practice new, more adaptive behaviors that support participation and success across settings.

Intervention is not designed to suppress behaviors but rather to build regulation, self-awareness, and adaptive responses through supportive, relationship-based, and developmentally appropriate strategies.

In practice, occupational therapists draw on a range of evidence-based and developmental strategies to support behavioral growth, including:

- Focus on self-regulation: OTs use frameworks such as The Zones of Regulation®, The Alert Program®, and other sensory-based strategies to help children identify their arousal states, interpret body cues, and choose tools that promote calm and focus.

- Behavioral management methods: When appropriate, OTs may integrate structured, evidence-based behavioral management programs—such as 1-2-3 Magic (Dr. Phelan), The Nurtured Heart Approach (Howard Glasser), or Positive Discipline (Dr. Nelsen)—to support consistency, clear boundaries, and positive behavior reinforcement. These approaches emphasize balanced, developmentally appropriate use of structure and consequences, helping children and families establish predictability and mutual respect. When used within an occupational therapy framework, these methods complement self-regulation, emotional awareness, and relational skill-building—without replacing psychotherapy or ABA.

- Environmental design: Behavior is influenced by the environment. OTs modify sensory input, physical setup, schedules, and routines to prevent dysregulation and reduce triggers.

- Collaborative coaching: OTs use coaching and education-based approaches to help parents, caregivers, and teachers understand their child’s sensory and emotional needs. Through modeling, reflection, and consistent practice, OTs support families in applying regulation and behavioral strategies across home, school, and community settings.

- Goal orientation: Behavioral change is achieved through improved sensory modulation, emotional regulation, and task fit, leading to genuine participation rather than surface-level compliance.

In short, OTs manage behavior from the inside out—building the foundations of self-awareness, regulation, and environmental support so children can thrive across home, school, and community settings.

Family Dynamics, Parenting Support, and Interpersonal Relationships

Occupational therapy is inherently family-centered. Children grow, learn, and self-regulate within the context of their relationships—so OTs work closely with parents and caregivers to strengthen the systems that support each child’s development.

Therapists help families understand how sensory, motor, emotional, and cognitive factors influence behavior and daily function. We collaborate to create predictable routines, reduce stress around daily tasks, and establish strategies that help everyone feel more connected and capable.

Parenting support may include developing structured routines, visual supports, and sensory-regulation tools that fit seamlessly into daily life. OTs also provide education and coaching to help caregivers interpret their child’s cues, respond effectively during moments of dysregulation, and promote independence while maintaining emotional connection.

In addition, OTs help families navigate interpersonal dynamics—supporting communication, role balance, and shared problem-solving among family members. By fostering understanding and compassion within the household, occupational therapy strengthens not only the child’s development but the well-being of the entire family system.

Self-Care and Activities of Daily Living (ADLs)

Self-care is a cornerstone of pediatric occupational therapy. OTs help children build the skills, routines, and confidence needed to participate in everyday activities such as dressing, feeding, hygiene, toileting, and grooming—promoting greater independence at home and school.

Intervention may include improving fine motor coordination, bilateral hand use, sequencing, sensory processing, and body awareness—skills that allow children to complete daily routines smoothly and confidently.

As children grow, these foundational self-care abilities expand into more complex daily living tasks—often referred to as instrumental activities of daily living (IADLs).

Instrumental Activities of Daily Living (IADLs)

As children mature, occupational therapists support their participation in more complex daily tasks that promote independence and prepare them for adolescence and adulthood. These “instrumental” activities build upon the foundation of self-care and include organizing school materials, managing homework routines, packing backpacks, preparing simple meals or snacks, participating in chores, and learning to plan and manage time. For teens, IADLs may expand to include money management, shopping, community navigation, and caring for others or pets.

By developing these higher-level life skills, OTs help children and adolescents build confidence, self-reliance, and readiness for the increasing demands of home, school, and community life.

Rest and Sleep

Healthy sleep routines are essential for emotional regulation, learning, and overall well-being. OTs evaluate how sensory preferences, daily habits, and environmental factors affect a child’s ability to fall asleep, stay asleep, and wake feeling rested. Therapists work closely with families to develop calming bedtime and wake-up routines, adapt the sleep environment for comfort and consistency, and integrate sensory or self-regulation strategies such as deep pressure input, rhythmic movement, or breathing exercises.

By addressing the sensory, environmental, and behavioral aspects of sleep, OTs help children and caregivers establish rhythms that promote rest, balance, and readiness for each day’s activities.

Health Management

Health management involves building awareness, habits, and routines that support physical and emotional well-being. For children, this may include learning to recognize body cues such as hunger, fatigue, or overstimulation; understanding and participating in health-related tasks like using inhalers, taking medication safely, or caring for braces or glasses; and developing organizational and time-management strategies that promote consistency in daily self-care.

Occupational therapists also work with families to build structure around nutrition, hydration, physical activity, and mindfulness practices, tailoring these routines to each child’s developmental and sensory profile. By addressing health management holistically, OTs empower children to take an active role in maintaining their well-being—laying the groundwork for lifelong self-care, confidence, and resilience.

Leisure

Leisure refers to the free-choice activities that bring enjoyment, relaxation, and fulfillment. For children, leisure often grows out of play but becomes more purposeful as they develop personal interests, hobbies, and ways to recharge. Occupational therapists help children and teens explore what they enjoy, identify barriers that limit participation, and build the skills needed to engage in meaningful recreational activities.

This may involve fostering confidence to join a sports team, encouraging creative outlets like art or music, or helping children find calming, screen-free ways to unwind. Supporting leisure allows children to experience balance—between learning, responsibility, and rest—while nurturing creativity, self-expression, and a positive sense of identity.

When self-care, instrumental activities, rest, health management, and leisure are addressed together, children develop balanced rhythms that support both physical independence and emotional regulation. By helping families create predictable, nurturing routines across morning, school, and bedtime transitions, occupational therapy fosters confidence, participation, and a sense of mastery in the tasks that shape everyday life.

Transition & Vocational Skills

For older children and teens, OTs help prepare for transitions to higher grades, community participation, and future employment. This includes teaching organization, time management, community navigation, and self-advocacy skills.

Assistive Technology & Environmental Adaptation

OTs recommend and train children in the use of adaptive tools such as pencil grips, slant boards, communication switches, and computer access devices. They also modify physical and sensory environments to promote accessibility and comfort.

Specialty Approaches: Aquatic & Equine OT

Beyond traditional settings, OTs may use water or horse movement as therapeutic tools. Aquatic OT enhances sensory-motor coordination; equine-assisted OT promotes balance, confidence, and emotional connection.

Liaison, Consultation, and Care Coordination

Occupational therapists often act as bridges between professionals, families, and systems of care. We collaborate with teachers, speech-language pathologists, psychologists, medical specialists, and other providers to ensure each child’s support plan is cohesive and effective.

Through regular communication and team meetings, OTs help align therapeutic goals across settings—making sure that strategies used at home, school, and in the community reinforce one another.

OTs also assist parents in assembling and coordinating an interdisciplinary care team, ensuring that every provider understands the child’s sensory, emotional, and functional profile. This collaborative model allows interventions to work synergistically, maximizing the child’s growth, participation, and success across environments.

Although occupational therapists are able to help in many ways, there are many other types of therapies that are highly beneficial in supporting children and families. Because occupational therapy encompasses such a broad scope of practice, it’s equally important to understand what falls outside of that scope. Recognizing these boundaries helps parents appreciate why they may work with an OT and another professional on similar goals—but in slightly different ways. It also highlights that the OT’s role may shift when other specialists are already fulfilling complementary aspects, such as serving as the primary care-team coordinator.

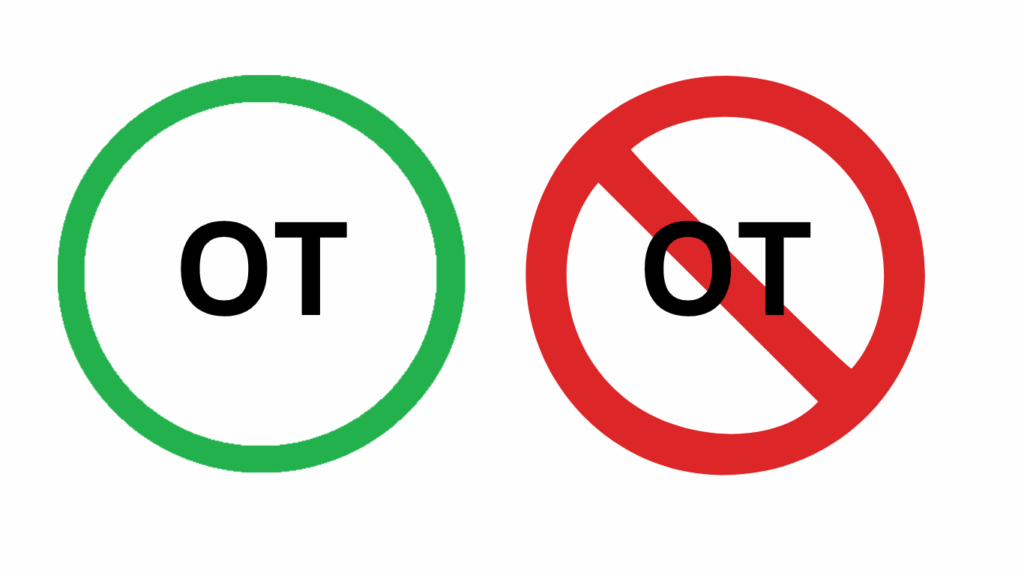

What OT Isn’t

While pediatric occupational therapy addresses the whole child—integrating sensory, motor, cognitive, emotional, and behavioral systems—OT is just one of many valuable supports a child may benefit from. What matters most is that children receive the right combination of services from providers who are a good fit, and that all professionals and caregivers work collaboratively for the child’s success.

Because occupational therapy has such a broad and integrative scope, it’s equally important to understand what OTs do not do. The following distinctions highlight how OT overlaps with—but remains distinct from—other disciplines such as speech therapy, physical therapy, psychology, and applied behavior analysis.

Not Physical Therapy

OTs and physical therapists (PTs) often share similar tools and techniques, and both address the musculoskeletal and neuromuscular systems to help children build strength, coordination, and body awareness. However, their focus and goals differ.

Physical therapists (PTs) specialize in the quality and mechanics of movement. They focus on alignment, strength, endurance, range of motion, and gait (walking) patterns, often addressing orthopedic, neurological, or developmental movement conditions. PTs are typically the professionals who evaluate and treat gait abnormalities, balance issues, and postural control, and in some cases, may diagnose or manage physical conditions related to motor function.

Occupational therapists (OTs) work on similar motor foundations—but always through the lens of function and participation. OTs address how strength, coordination, and balance translate into meaningful daily skills such as dressing, writing, feeding, or sitting upright in class. They integrate sensory, cognitive, emotional, and physical systems to help children use their bodies purposefully and confidently across home, school, and play settings.

In many pediatric programs, OTs and PTs work side by side—PTs supporting how the body moves, and OTs focusing on what that movement allows a child to do. Together, they provide a holistic approach that nurtures growth, independence, and everyday success.

Not Speech Therapy

OTs may address feeding and oral-motor mechanics (chewing, swallowing, posture for feeding), but they do not provide therapy for articulation, expressive/receptive language, or fluency. These are within the expertise of speech-language pathologists (SLPs).

Not ABA Therapy

While OTs address behavioral management, they do so from a developmental, sensory, and emotional regulation perspective—not through the strict operant-conditioning framework of Applied Behavior Analysis (ABA).

- OT focuses on understanding why behaviors occur — by exploring sensory needs, emotional regulation, cognitive processes, and how the environment fits the child.

- ABA focuses on modifying which behaviors occur — using reinforcement, structured teaching, and behavior analytic techniques to increase desirable behaviors and reduce undesired ones.

Together, they can complement each other—ABA supports measurable skill learning, and OT builds the internal and environmental foundations that sustain it.

Not Psychotherapy

Occupational therapists absolutely address aspects of mental health—such as emotional regulation, stress management, social participation, and coping within daily routines—but they do not provide psychotherapy or clinical mental-health treatment. Processing trauma, family conflict, or deeper emotional patterns falls within the expertise of psychologists, marriage and family therapists (MFTs), or licensed clinical social workers (LCSWs).

- OT focus: Supporting mental health through participation—helping children recognize emotions, use sensory or movement-based regulation tools, develop coping routines, and build confidence in daily roles (home, school, play).

- Psychotherapy focus: Exploring the roots of emotional distress—such as trauma, relationships, or thought patterns—through talk therapy, play therapy, or other relational methods to promote emotional healing and insight.

Together, these disciplines complement each other: OT helps children manage daily life and strengthen regulation skills, while psychotherapy provides deeper emotional processing and long-term psychological healing.

Not Educational Therapy

While OTs address skills that support learning—such as attention, executive functioning, visual–motor integration, and self-regulation—they are not educational therapists. Educational therapists primarily provide academic intervention, remediation, and tutoring for specific learning differences (e.g., dyslexia, dyscalculia, ADHD-related study skills). In contrast, occupational therapists focus on the underlying developmental and functional foundations that make learning possible: sensory processing, posture, motor coordination, attention, and participation in classroom routines. OTs often collaborate with educational therapists and teachers to ensure a child’s functional skills and learning strategies work hand in hand.

Not Vision Therapy

Occupational therapists address visual–perceptual, visual–motor, and oculomotor skills as they relate to participation in daily activities like reading, writing, and play. However, OTs are not vision therapists and do not prescribe or provide interventions involving prisms, colored lenses, or optical corrections. Vision therapy is within the scope of a developmental optometrist or ophthalmologist. OTs and optometrists often collaborate—OT focuses on functional participation and environmental adaptation, while the optometrist addresses visual efficiency and eye health.

Conclusion

Pediatric occupational therapists support the whole child—addressing sensory, motor, cognitive, emotional, and behavioral systems together. Through evidence-based practice, collaboration, and thoughtful environmental design, OTs help children participate meaningfully in the daily occupations that shape their growth and well-being.

With that being said, occupational therapy is just one of many valuable supports a child may benefit from. What matters most is that each child receives the right combination of services—from providers who are a good fit—and that all professionals and caregivers work collaboratively for the child’s success.

OTs also recognize that a child’s well-being is shaped not only by direct therapy, but by the environments and relationships that surround them. By partnering with families, teachers, and other care providers, OTs help design spaces, routines, and interactions that nurture participation, confidence, and connection across all areas of daily life.

Resources for Further Exploration

Core AOTA Frameworks and Standards

– American Occupational Therapy Association. (2020). Occupational Therapy Practice Framework: Domain and Process (4th ed.). American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 74. (Suppl. 2). https://research.aota.org/ajot/article/74/Supplement_2/7412410010p1/6486

– American Occupational Therapy Association. (2021). Standards of Practice for Occupational Therapy. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 75 (Suppl. 3). https://research.aota.org/ajot/article/75/Supplement_3/7513410030/23113

– American Occupational Therapy Association. (2021). Guidelines for Occupational Therapy Services in School-Based Practice. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 75 (Suppl. 3). https://research.aota.org/ajot/article/75/Supplement_3/7513410060/23118

– American Occupational Therapy Association. (2021). Scope of Practice Chart. https://www.aota.org/-/media/corporate/files/advocacy/scope-of-practice-chart-10-21.pdf

– American Occupational Therapy Association. (2022). Model Occupational Therapy Practice Act. https://www.aota.org/-/media/corporate/files/advocacy/state/resources/practiceact/final-model-practice-act-2022.pdf

– American Occupational Therapy Association. (2017). Occupational Therapy’s Role in Physical Rehabilitation. OT Practice.

–American Occupational Therapy Association. (2015). The Role of Occupational Therapy in Rehabilitation for Individuals with Neuromuscular Conditions. AOTA Fact Sheet.

-Case-Smith, J., & O’Brien, J. C. (2015). Occupational Therapy for Children and Adolescents (7th ed.). Elsevier.

Sensory Integration, Social-Emotional Learning, and Collaboration

– Schaaf, R. C., et al. (2021). Effectiveness of Occupational Therapy Using a Sensory Integration Intervention for Children with Developmental Disorders. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 75 (6).

– Bazyk, S., & Bazyk, J. (2021). Fostering Social Participation and Emotional Well-Being in Children Through Occupational Therapy. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 75 (3).

– Ward, S. C., et al. (2020). Collaboration Between Behavior Analysts and Occupational Therapy Practitioners. Behavior Analysis in Practice, 13 (4).

– Dunn, W. (2014). Sensory Processing Frameworks and Everyday Participation. AOTA Press.

– Williams, M. S., & Shellenberger, S. (1996). How Does Your Engine Run? The Alert Program® for Self-Regulation. TherapyWorks, Inc.

– Kuypers, L. (2011). The Zones of Regulation®. Think Social Publishing.

– Frick, S., & Young, S. (2009). Listening With the Whole Body: Therapeutic Listening® and Sensory Integration. Vital Links.

Specialty Practice Areas

– American Occupational Therapy Association. (2023). Spotlight on Pediatric Aquatic Occupational Therapy. https://www.aota.org/about/for-the-media/aquatic-occupational-therapy

– American Occupational Therapy Association. (2023). Incorporating Hippotherapy in the Treatment of Pediatric Populations. OT Practice.

– American Occupational Therapy Association. (2018). Role of OT in Comprehensive Integrative Pain Management. https://www.aota.org/-/media/corporate/files/practice/role-of-ot-in-comprehensive-integrative-pain-management.pdf

– American Occupational Therapy Association. (2023). Social and Emotional Learning Info Sheet. https://www.aota.org/-/media/Corporate/Files/Practice/Children/SchoolMHToolkit/Social-and-Emotional-Learning-Info-Sheet.pdf